-

-

1880s

SOMALILAND PROTECTORATE

In the 16th century, Zeila was occupied and annexed by the Ottoman Empire as a port town. In the 1880s Europeans (Britain, Italy and France) began disputing with each other for control for spheres of political influence in Africa. At the turn of the 19th century, when the Ottoman Empire weakened was on the brink of collapse, Egypt which was a vassal of the Ottoman, Empire occupied the western parts of Somaliland.

Our history

- Somaliland presidency

- Our history

History of Somaliland

1880s

1905

-

-

1905 to 1913

Military activities in the Somaliland Protectorate

For centuries, Somali people in the Horn of Africa practiced nomadic pastoralism, moving across regions in search of pasture. This lifestyle led to their presence across Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, Somaliland, and Djibouti. Despite being spread out, Somalis share a common identity through language, religion, and culture. A unified Somali nationalism only emerged during colonial times, with the idea of uniting all Somalis under one nation. Historically, Somalis had ties with neighboring communities, especially Ethiopians, dating back to the 13th century. During the colonial scramble for Africa, Emperor Menelik of Ethiopia sought territorial expansion, claiming Somali-inhabited regions with European approval. In 1889, he and his governor Ras Mekenon annexed parts of Somali territory.

-

1950-1960

Flag of British Somaliland

As Somaliland became part of the British Empire there was the necessity for the defining and delimiting the borders of the protectorate with the neighboring territories of Ethiopia, the French territory of Djibouti and Italian Somalia.

-

1960

-

-

February 17 1960

The First Somaliland Parliament

Towards the final years of the colonial period and in preparations for independence, legislative elections were held on February 1960. A number of political parties took part. The Somali National League (SNL) which originated from the Somali National Society (SNS); the National United Front (NUF aka NAFTA); and the United Somali Party (USP) participated in the elections. SNL won the elections with a sliding majority (20 out a total of the 33 seats contested); the USP party (12 seats) and the NUF party (1 seat). The first elected Legislative Council (Cabinet) were: Mohamed Haji Ibrahim Egal (First Minister); Garad Ali Garad Jama (member); Haji Ibrahim Nur (member); Ahmed Haji Duale (Ahmed Kayse) (member) and Haji Yusuf Iman (member).

-

THE UNION

At the time of independence there was a strong anti-colonial sentiment sweeping the African continent. Somaliland was no exception. There was a popular drive to unite all the five Somali inhabited territories including Somaliland, Somalia, French Somaliland (Djibouti), Ogaden (Ethiopia), and the Northern Frontier District (NFD) of Kenya. The five-pointed white star on the flag symbolized this aspiration. The 1954 Anglo-Ethiopian Agreement in which Britain transferred 25,000 sq miles (64,750 sq km) of ‘Hawd’ grazing land to Ethiopia evoked an outcry in Somaliland and intensified the demand for a union to recover lost territory. Under public pressure, Somaliland and Somalia representatives opened a dialogue on a union between the two territories. The two parties agreed to sign an act of Union after independence. They agreed that the act would be in the nature of an international agreement between two states. Accordingly, the Legislative Assembly of the independent State of Somaliland approved and signed the Union of Somaliland and Somalia Law on 27 June 1960. The Law was immediately effective in Somaliland, but as set out in the recital, it was supposed to be signed by the representatives of Somalia, as well. In fact, this never happened. Instead, the Legislative Assembly of the Somalia Trust Territory met on 30 June 1960 and decided to approve “in principle” an Act of Union (Atto di Unioni), which was significantly different from the Act of Union drafted by Somaliland assembly. According to Contini, (The Somali Republic: An Experiment in Legal Integration, Frank Cass & Co. Lt 1969: London), the Assembly requested the “Government of Somalia to establish with the Government of Somaliland a definitive single text of the Act of Union, to be submitted to the National Assembly for approval”. But on the morning of 1st July 1960, the members of the Somaliland Legislative (33) and those of the Somalia Legislative (90) met in a joint session and the Constitution which was drafted in Somalia was accepted on the basis of an acclamation, with no discussion, and a Provisional President was elected. The newly elected Provisional President issued on the same day a decree aiming to formalize the union, but even that was never converted into Law as presidential decrees always require to be presented to the National Assembly for conversion into Law under Article 63(3) of the new Constitution within five days of their publication, otherwise, they shall cease to have effect from their date of issue. Thus, although the agreement between Somaliland and Somalia was that the same Act of Union would be signed by both states, that did not happen and the legal formalities were not completed properly as agreed. According to Contini, “the Union of Somaliland and Somalia Law did not have any legal validity in the South (Somalia) and the approval “in principle” of the Atto di Unione was not sufficient to make it legally binding in that territory.” Cotran [(1968)12 ICLQ 1010] comments that the legal validity of the legislative instruments establishing the union was “questionable” and he summarized the reasons as follows: The Union of Somaliland and Somalia Law, and the Somalia Act of Union were both drafted in the form of bilateral agreements, but neither of them was signed by the representatives of the two territories. The Union of Somaliland and Somalia Law purported to derogate in some respects from the Constitution of the Somali Republic. The Somalia Act of Union was approved “in principle” but never enacted into law. The decree law of July 1, 1960, did not come into effect since it was not converted into law in accordance with the Constitution.” It was only on 18 January 1961 when a new Act of Union was put to the National Assembly and was promulgated on 31 January 1961. This Law entitled the “Act of Union” was made retrospective even though there is a generally accepted principle that laws should not be retroactive. The new Act of Union was different from the one signed by the Somaliland Legislature. The Law of Union passed by the Somaliland Legislature contained some guarantees about the laws applicable in Somaliland, the rights of Somaliland serving officers, which should not become less favorable than was applicable to them at the time of the union, the establishment of a special Commission on laws and its composition etc. These were, in hindsight, the only, rather halfhearted, demands that Somaliland made at the time of the union. But the 1961 retrospective Act was very clear in repealing anything which was inconsistent with the 1960 Somalia Constitution, and specifically repealed “the provisions of the Union of Somaliland and Somalia (Law No.1 of 1960)” except for Article 11(4) which relates to agreements entered into by the independent State of Somaliland (see Article 9(2) of the 1961 Act of Union). The above is a clear indication that Somaliland was an independent state with a Government of its own, however short lived. This was again confirmed by Article 11(4) of the 1961 Act of Union, which read: “all rights lawfully vested in or obligations lawfully incurred by the independent Governments of Somaliland and Somalia … shall be deemed to have been transferred to and accepted by the Somali Republic upon its establishment”. On 20 June 1961 a constitutional referendum was held to vote on the new constitution for the country created the previous year by the union of British Somaliland and Italian Somalia. The constitution was overwhelmingly approved by Somalia voters. But, in Somaliland, the referendum was boycotted by the leading political party, the Somali National League (SNL), as a result only 100,000 votes were casted, and 60% of those voted opposed the provisional constitution.

-

1981

-

-

April 12 1981

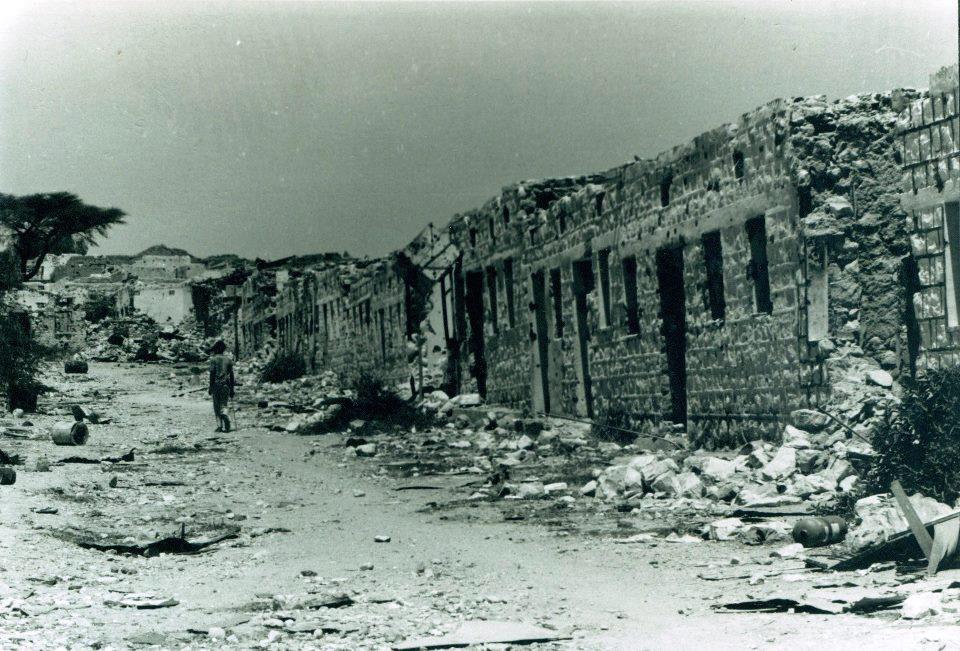

WAR AND CRIME

In response to the targeted harsh policies enacted by Siad Barre against the people of Somaliland, a group of social and political activists established the Somali National Movement (SNM) in April 12 1981 in London. By 1982, The SNM, transformed into a liberation front which engaged the Somali National Army in hit and run operations. The government took revenge on the people for the SNM activities. According to 1990 Africa Watch report, ‘Both the urban population and the nomads living in the country side have been subjected to summary killings, arbitrary arrest, detention in squalid conditions, torture, rape, crippling constraints on freedom of movement and expression and a pattern of psychological intimidations. ‘ On May 27, 1988, the SNM launched a surprise attack on Burao, followed by another attack on Hargeisa on May 31. The operation was successful against all odds and the movement managed to hold onto parts of the two cities for days. The government responded with a massacre of the civilian population. The number of civilian deaths in the ensued carnage is estimated between 50,000- 100,000. The government attacks included the leveling and complete destruction of Hargeisa through a campaign of aerial bombardment. This has lead to more than 400,000 people fleeing their homes and crossing borders to seek sanctuary in refugee camps in Ethiopia. Another 400, 000 became internally displaced. The infamous letter, ‘the Final Solution’, written by General Mohamed Saed Hirsi, the commander of the 26th regiment in the ‘North’ (Somaliland) to Siyad Bare, on January 17, 1978 revealed the intention of the regime to eliminate the majority community in Somaliland. In 2001, the United Nations commissioned an investigation on past human rights violations in Somalia, specifically to find out if "crimes of international jurisdiction (i.e. war crimes, crimes against humanity or genocide) had been perpetrated during the country's civil war". The investigation was commissioned jointly by the United Nations Co-ordination Unit (UNCU) and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. The investigation concluded with a report confirming the crime of genocide to have taken place against the Isaaqs (the majority community) in Somalia.

-

1991

RECONCILIATION

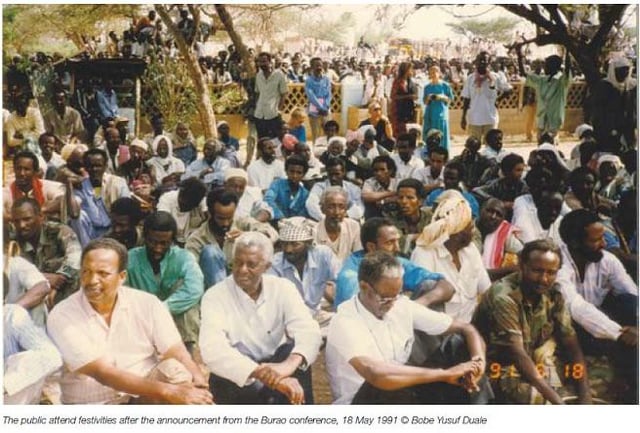

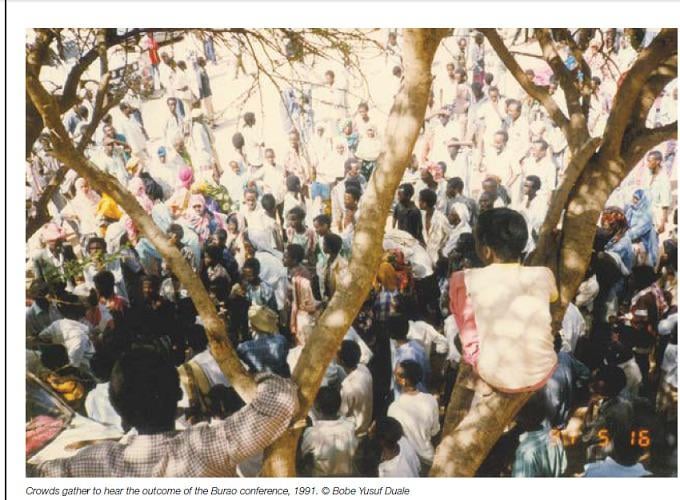

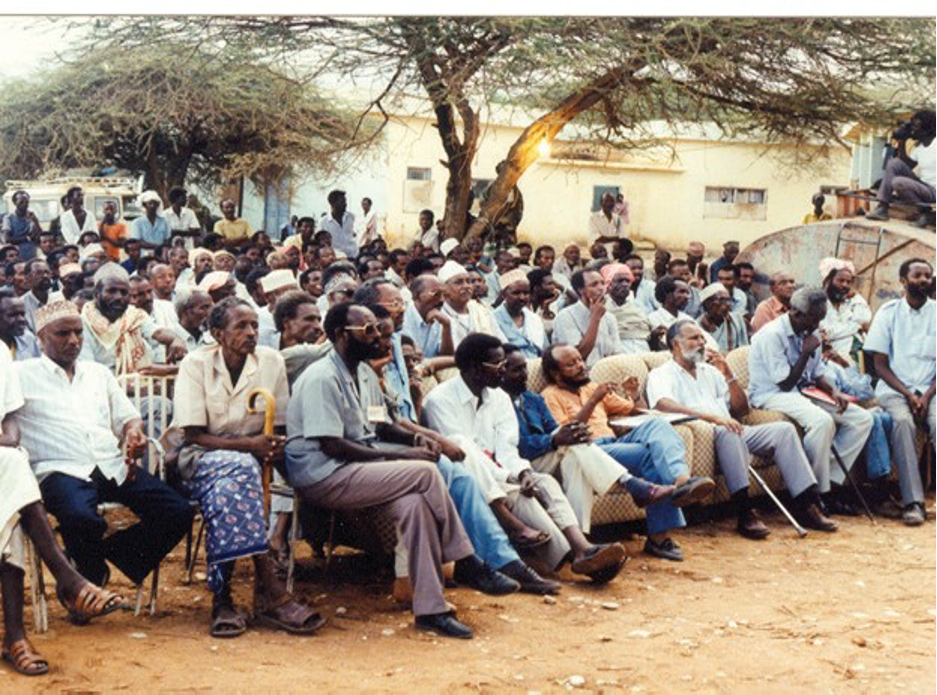

After the liberation of the country and the collapse of the regime in Mogadishu, the people of Somaliland embarked on a series reconciliation conferences including:

February 1991 Berbera conference

April-May 1991 Burao conference

October 1992 Sheikh conference

Jan-May 1993 Borama conference

September 1996 Beer conference

October 1996- February 1997 Hargeisa conference

These meetings were attended by representatives of a broad spectrum of the community including traditional leaders, religious leaders, SNM leadership, politicians, intellectuals, businessmen, and members from the Diaspora community. The main purpose was to make peace, resolve conflict, reconcile differences, build confidence, demobilize militias, and transit from SNM based governance structure to a broader community/clan-based system. These conferences laid the foundation for the new Somaliland state. -

1991

-

-

May 18, 1991

DEMOCRACY AND STATE BUILDING

Collective decision-making is part of the tradition of Somaliland. The SNM, the precursor to the Somaliland government, was an inclusive democratic institution that changed leadership democratically five times in a span of 10 years. That tradition was carried on by the successive governments that ensued.

1991-93

-

-

May 1991 – May 1993

Elected The 1st President of Somaliland

Abdirahman Ahmed Ali Tuur was elected the first president of Somaliland by delegates and was sworn in as president on June 7, 1991

-

May 5, 1993

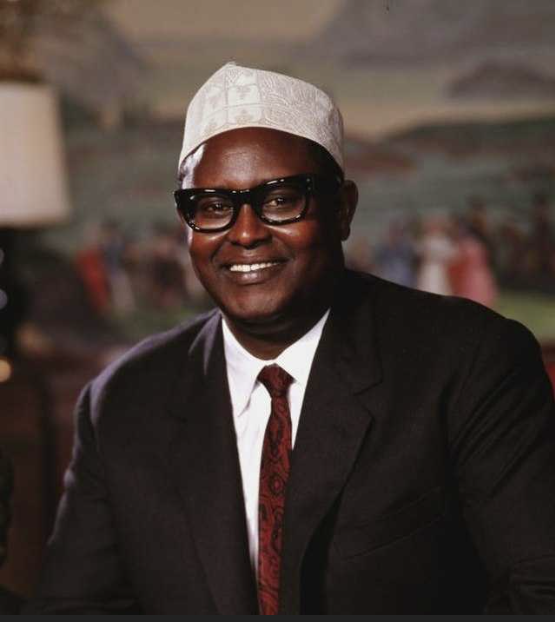

Elected The 2nd President of Somaliland

Mohammad H. Ibrahim Egal was elected president of Somaliland at Borama conference and was inaugurated as president on May 16, 1993. The National Charter, the precursor of the Somaliland constitution, was adopted.

-

1997

-

-

May 1993 – May 2002

Re-elected President Egal

President Mohammad Ibrahim Egal was re-elected by the National Communities Conference (meeting as an electoral college), and an interim constitution was approved.

-

May 4, 2002

President Egal died in Pretoria, South Africa, and Vice-President Dahir Riyale Kahin was sworn in as president of Somaliland on May 4, 2002

-

2002

-

-

May 2002 – July 2010

Dahir Riyale Kahin was elected The 3rd President of The Republic of Somaliland

-

April 14, 2003

President Dahir Riyale Kahin of the United Peoples’ Democratic Party (Ururka Dimuqraadiga Ummadda Bahawday – UDUB) was

re-elected -

2010

-

-

July 2010 – December 2017

Ahmed Mahamoud Silanyo of Kulmiye party was elected The Fourth president of The Republic of Somaliland

Ahmed Mahamoud Silanyo of Kulmiye party was elected president and was inaugurated as president on July 27, 2010. This was the second presidential election by popular vote. The election was declared free and fair by more than 70 international observers.

-

November 28, 2012

The second local elections were held. 50 international election observers from 17 countries monitored the local elections which were declared free and fair

-

2017

-

-

December 2017 – December 2024

Muse Behi Abdi of Kulmiye part was elected The 5th President of The Republic of Somaliland

-

The third presidential election was held. Muse Behi Abdi of Kulmiye part was elected and was inaugurated on December 13, 2017. 60 observers from 27 countries declared that they have witnessed a poll that preserved the integrity of the electoral process.

-

2024

-

-

December 2024 – Present

Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi “Irro” was elected The 6th President of The Republic of Somaliland

-

in December 2024, Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi “Irro” was elected president, marking another peaceful transition. A veteran politician and opposition leader, Irro’s administration has pledged to pursue international recognition, enhance democratic institutions, and expand economic opportunities.

-